The thought that motivated this essay was: A discounted cash flow model is the way to value any stream of earnings, but don’t investors like Buffett and Munger price things in practice? What is a fair price for a wonderful company?

My hunch going into this was that nobody with decades of experience in the market stakes every investment decision with a full DCF exercise. They instead develop an intuitive judgment for good price floors over time. I had three reasons for this hunch:

- The US equities market grows more expensive each year and quality businesses fetch high premiums. Even the most disciplined of investors has to reevaluate their opportunity cost and pay for some growth today. A DCF model can’t tell you how much that should be, it has to be a judgment call for a price floor

- If you’ve worked through a DCF model at least once, you appreciate how your uncertainties for a few variables (pricing power, sales growth, profit margins, returns on incremental capital, etc.) affect the results. So we know it’s more important to work on developing reasonable distributions of estimates for the value drivers, and therefore a fuzzy range of possible yields on an investment for a given price, than it is to focus on modeling one set of financial projections

- Buffett, Munger and other famous investors tend to spend more time discussing the psychology of investing than modeling. They talk about waiting for obvious mispricing opportunities, not straying from one’s circle of competence, grounding assumptions about the future in history (base rates) and updating beliefs as new information materializes. All of these support the preceding point, that research time is well spent comparing our expectations about a company or industry against those of the market

I learned two things. First, other people have asked this question before and spent time answering it. I’ll be recapping their findings and add some of my own. Second, Buffett’s Berkshire-era purchases in the stock market and acquisitions tend to cluster around 10 times pretax profits, peaking at 15 turns. This price range is consistent across time and sectors. It’s equivalent to 15 to 20 times earnings, which is at or slightly above the historic S&P 500 median multiple. Buffett buys at these prices when he can expect at least 10% in pretax income growth on his investment.

A big limitation of this analysis is that I haven’t looked as much into how Buffett finds and identifies companies for purchase. There are at least two solid books that reverse-engineer his investments. But if making money in the stock market means paying cheap prices for quality companies, then developing a feel for prices is fighting some of the battle.

Buffett applies the same filters for equities and acquisitions

Let’s look at some of the prices Buffett has paid throughout his career. He and Munger bought See’s Candies, their “dream business”, at 6.25 times pretax profits ex cash or about nine times pretax profits gross (Munger said in 2020 that there was $10 million surplus on the balance sheets). Lower is better: Buffett views buying a high-quality company at five to seven times earnings before taxes as a great deal (1984 LTS).

At the 2012 annual meeting, Buffett answered a question on valuing Berkshire’s noninsurance earnings that he’d buy businesses similar to Berkshire’s “certainly nine times pretax earnings, maybe 10 times. […] If they have similar characteristics, we’d probably pay a little more than that, because we know so much more about them than we might know about some other businesses.” In 2024, Berkshire completed its acquisition of Pilot Travel Centers at 10 times operating earnings. Bill Ackman has noted Buffett’s price discipline at this level too.

The topic of Buffett applying this multiple to equity purchases saw a rise in popularity in 2014, when Brooklyn Investor wrote a popular blog post about Berkshire’s investments in Coca-Cola, American Express and other companies. A commenter in the post mentioned Buffett purchasing McDonald’s at 10 turns in 1990. In 2022, Todd Combs outlined how he and Buffett found Apple in 2016 by screening with the following questions: “How many names in the S&P are going to be 15 times earnings [10 times pretax profits] in the next 12 months? How many are going to earn more in five years (using a 90% confidence interval), and how many will compound at 7% [10% pretax income growth] (using a 50% confidence interval)?”

Buffett has at times made concentrated bets at up to 15 times pretax profits in equities. Notably, he stops buying beyond that price. Between 1963 and 1964, he invested 40% of his partnership money into Amex as prices rose to 13 times pretax earnings. He described the company as being a “relatively undervalued general [large-cap company]”. In 2000, he invested in Moody’s as it was spun out of its parent company at $20.70 per share. The 1999 pretax earnings per share was $1.65, so he paid at almost 13 turns again. Buffett has also paid this price for Tesco (a loss), Precision Castparts (had an asset impairment charge) and parts of Apple.

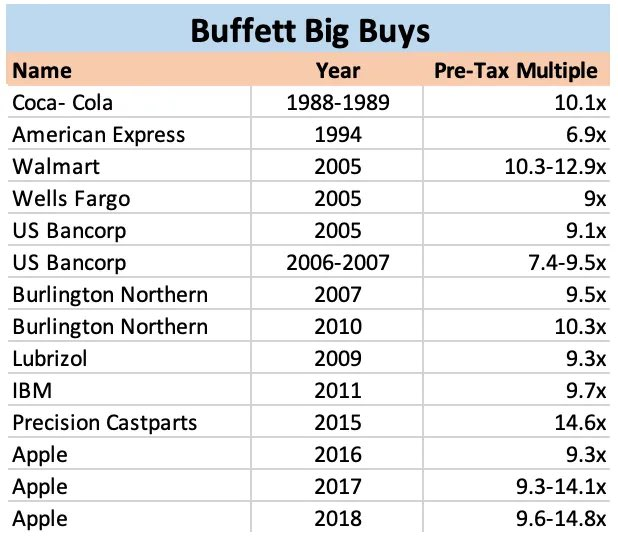

The chart below, courtesy of Michael Kandolin via Twitter, summarizes prices Buffett paid for Berkshire’s biggest investments. Full disclosure: I can’t say the data in this table is bulletproof, not least because it’s hard to do so with quarterly disclosures and market prices, but it conveys the larger point. I used Berkshire’s letters to validate the multiples only for IBM, Apple and Walmart. While IBM and Apple’s multiples here make sense, Walmart was a one-time purchase for about 13 turns. In the same vein, Berkshire bought Coca-Cola on and off for seven years, yet only the entry multiple is quoted.

Backing out Buffett’s valuation philosophy from the prices he’s paid

Buffett’s buying behavior shows that he prices equities as private acquisitions. But why?

Buffett draws on Graham when he says, all else equal, the decision process to buy one share in a publicly traded company and buying it outright should be identical. If we are investing in a company we like run by excellent management, it doesn’t matter that we don’t have control. Indeed, we’d want the managers to do what they do best. Our ownership in either scenario entitles us to a proportionate share of retained earnings.

What are the implications of this philosophy? For Buffett, an attractive buying price for a company is one that’s below the typical cost of taking a comparable company private. He has used this definition in some letters from the 1980s. This mean, conditioning on company characteristics, we can use the historic private equity average as a price floor.

It’s common practice in private equity to price companies as a multiple of some measure of its most recent full-year net operating cash flows. Buffett and Munger reject EBITDA and private equity’s use of that metric, preferring instead to price in pretax profit dollars.

The 10 turns pretax multiple is consistent with the S&P 500’s historical median 15 turns PE. Buffett has built a portfolio of high-quality companies for Berkshire at that price. Relative to the index, a group of above-average companies bought at an average price will outperform in annualized returns.

The purchase multiples being consistent across industries and time show that Buffett only cares about the quality and certainty of cash flows. It echoes his attitude towards capital risk: the volatility of the asset price doesn’t matter. Instead, what matters is your surety around the amounts and timings of cash flows from the asset to your share.

But that shouldn’t mean any multiple is a good price for those cash flows as long as its guaranteed and is below the S&P average. In his 2002 letter to shareholders, Buffett says he wants a minimum of 10% pretax yield on either an acquisition or purchasing equities. The choice of the 10% pretax returns is consistent with:

- An after-tax return on 10% constant yields will be at least as good as the pretax return on the average US long-term riskfree rate of 6.5%

- The S&P 500’s long-term gain. The index is Berkshire’s performance benchmark for and Buffett’s choice for passive holdings

The total shareholder returns formula lets us combine the multiple and yield criteria in one equation: TSR = price appreciation x [(1 + price appreciation) x dividend yield] where price appreciation = earnings per share growth x PE multiple change x change in shares outstanding. (We can use pretax earnings and multiples for an equivalent formulation.)

A good investment returns at least a hurdle rate in TSR without the multiple paid not eating into returns. On rare occasions, owning a company at a high entry multiple is worth it when the the multiple contraction is outweighed by earnings growth and buybacks. This is what John Huber points outin the case of Google.

All of this ties in with Buffett’s version of Aesop’s fable (2000 LTS), rephrasing mine:

- Given the market cap of the company, what’s the expected range of annualized TSR over your desired holding period? Does the price protect against multiple deterioration eating into returns?

- What’s your 90% confidence interval on that range of returns? If zero is in the interval, then pass

- Does the lower end of the interval exceed the riskfree rate? Here, 10% is the pretax equivalent rate when the S&P 500 is an option

If we can answer these questions for new investment opportunities, we can then compare their potential returns to your current holdings’ to decide what to buy. In the same vein, we could sell all or part of a holding when its expected returns no longer meet the criteria and then buy the next best option.

Takeaways for the rest of us

Is this a good approach for valuation for the retail investor? While I am not running Berkshire, I can still think in opportunity costs and view my piddling investment portfolio as a collection of companies I own.

By default, my wife and I throw our money into S&P500 index funds. That means an equity/bond/real estate choice will be better than the index when it:

- has prospects at least as good as that of a typical S&P 500 business: staying power in the market, profitable and predictable future returns that will at least keep up with inflation

- is available at a price that is a reasonable floor and yields 10%+ pretax returns with 90% confidence on day 1

Practicing this framework demands expertise in analyzing businesses to a high degree of confidence and patience in waiting for the right prices. Building a defensible confidence interval of returns for each company requires command of base rates for reference classes. And even then I may be out of luck. For example, if I focus on technology companies and find prices never exceed sub-10% yields, I’d find myself sitting on my hands a lot. I’d be better off throwing money into VOO and watching it grow.

While an average price offers protection from multiple deterioration and a hurdle rate safeguards from mania, this approach won’t save investors from downside risk. For example, if the company’s sector will be in permanent decline after you invest, the best thing is to get out while you can. Indeed, this is what has happened with Berkshire’s investments in retail and airlines.

It makes sense then why people talk about having the right mental mindset for this game. Despite your best efforts, some proportion of your forecasts will be wrong and you need to reevaluate the investment. The sunk cost fallacy and denial are impediments in these situations.

A meta note on this post

I have been cooking since college. I am decent at it. It helps that I like to eat. Now, I enjoy learning about how chefs work in professional kitchens. Since I have developed tastes as eater and cook over time, I am good at filtering in recipes and techniques that work for me and my family.

I lack the same self-knowledge, experience and confidence on investments at the moment. The big reason is I haven’t seriously and sustainably studied companies yet. So as I researched Buffett’s buying activities, I felt like somebody who doesn’t know how to boil water studying how chefs run dinner service.

I needed to write this post to shift my brain from fixating on the best prices to analyzing businesses. I also had to synthesize everything I have learned about prices from Buffett rather than worship him and take his numbers as gospel.