I discovered this paper by Scott Abrahams and Frank S. Levy, via a Times article from a week ago.

The paper’s central prediction is: companies will substitute LLMs for college grads → Demand for four-year degrees will fall → Fewer people will move to big cities (where the college-graduate jobs concentrate) and instead choose to settle in smaller, cheaper cities → Political polarization between regions will fall as regional concentrations of college-educated workers fall.

What follows below are my reactions to reading the Times piece and the paper’s abstract, conclusion and introduction sections.

On the paper

After reading the abstract, I was skeptical of the paper’s grand prediction. Predicting big changes in labor demand and migration due to LLMs is remarkable already, then extrapolating to shifts in political alignment is bold. I wouldn’t react as much to that story if I read it in an op-ed, but it seemed like a big leap in a single research paper. Here’s key parts of the abstract quoted:

Combining our mapping [of LLM impacts on labor demand] with [post-1980 US manufacturing decline effects on US employment] avenues, we predict that displaced college graduates will migrate towards smaller, lower exposure urban centers including Rochester, New York and Savannah, Georgia, that demand for a four-year college education will fall, and that the migration patterns and politics of affected persons will dampen rather than exacerbate political polarization […]

I have two pieces of criticism for this study:

Analogizing LLMs to manufacturing decline

The authors’ comparison of LLM impacts on labor demand with the post-1980 US manufacturing decline effects is apples-to-oranges. When companies globalized, they moved factories from one region to cheaper ones. They didn’t wholesale replace American workers with robots and somehow still retain domestic production, which is the extreme outcome we imagine with white-collar jobs and generative AI.

A comparison to Web-enabled automation would have been more apt and yielded different conclusions. This would have shown how malemployment in the college grad labor market would be an important immediate consequence of companies automating jobs and reducing full-time equivalent headcount. Adopting the Web significantly reduced the need for dedicated back office personnel, travel agents, customer support, etc. But we were back on the hedonic treadmill and demanding our admin costs be further minimized, travel be cheaper, and troubles be shot faster. SaaS companies profited by meeting this demand with digital platforms and hiring people in contracted supporting roles with minimized pay and scope for college-educated workers. These firms also invested in engineering talent to build the platforms. This shifted returns from specific majors to STEM, while the overall expected return from a college degree increased. As for shifts in labor migration or political polarization, social media didn’t dissuade us moving to big cities and rendered us even more politically polarized.

Before I read this paper, I expected that its prediction would be that adopting LLMs will continue what the post-2000 Web adoption started. I maintain that is the better analogy. In order to determine society’s/economy’s response to LLM disruption of white-collar jobs, we have to first assess how we poorly responded to Web disruption and allowed the gig economy to take off without adequate worker protection.

The authors would probably respond that they want to leverage lessons of recent history of big impacts to a specific labor class and that Web adoption (particularly through smartphones) is relatively new and things are in flux. I think the authors used the manufacturing decline data because it was available, but it’s not the best analogue.

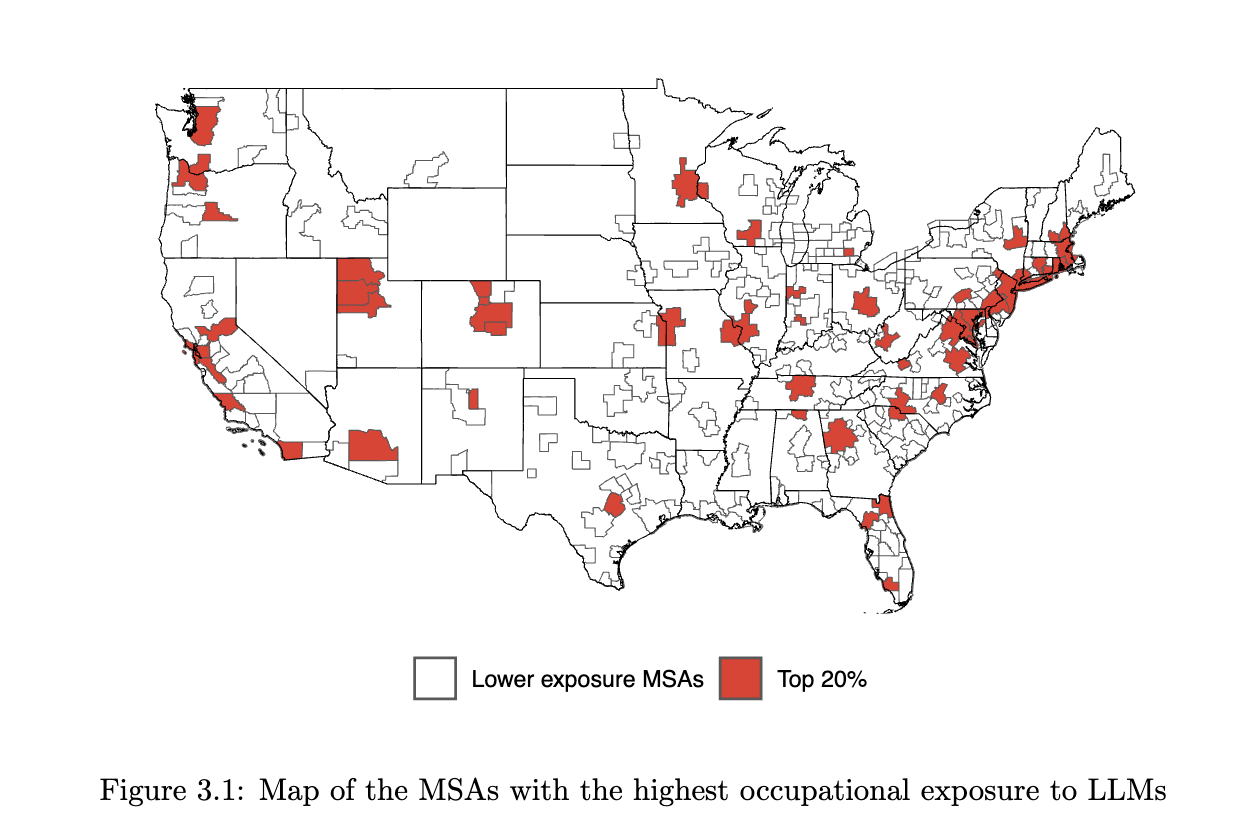

The paper used the manufacturing decline framework to produce this map of exposure to LLM shocks, based on current concentrations of jobs that require college degrees or more. “Exposure” means an LLM can automate at least part of a worker’s job, requiring fewer workers overall to produce a fixed amount of output.

This maps shows that the top 20% of exposure is for large urban centers (DC, LA, SF, NY) that (i) have lots of white-collar jobs requiring college degrees and (ii) vote Democrat. This is the basis for the authors’ predictions above.

Predicting college degrees won’t matter as much

Let’s move past the choice of comparison to one of the key predictions. It’s tough to fully buy the argument that the demand for college degrees will fall based on labor automation alone. LLMs, like the Web before it, won’t replace credentialism in society or the signaling value of college degrees. Students will demand degrees to compete in the labor market, even if degrees are no longer the main selling points of their resumes. There’s also a vast literature measuring the non-pecuniary aspects of college degrees, like networking and internships, that suggests universities aren’t at risk of going out of business.

I agree on the political economy of generative AI development

In their conclusion, I appreciated the sobering reminder that LLM development and political influence is concentrated in the hands of a few powerful players like Google and Microsoft that already have network effects working in their favor. This oligopolistic nature of generative AI R&D alone should motivate us to regulate technology companies and support all affected labor, but doing either will be hard without political support.

Software companies have long argued that they can regulate themselves. There are reasons to be skeptical. In recent decades, many software technologies have tended toward a few dominant firms driven by network externalities. The dominant firms and their management became extremely wealthy as a result.

AI software—in particular LLMs—reinforces this tendency toward dominant firms and concentrated money. Developing and training an LLM is extremely expensive both in terms of computational time and in data and power requirements. One result is that university researchers are priced out of developing this technology […]. A second result is that the LLM industry is dominated by a few firms. […] Given the firms’ economic power and the importance of money in current political life, the outcome of a government/industry contest is not easy to predict.

A slight technical silver lining is that open-source LLMs are gaining ground on proprietary models on measures of performance and cost. But it’s true and much more relevant that that the moat of LLM-based Big Tech services isn’t the choice of model, it’s the powerful effect of bundling LLMs with existing networks, platforms and data.

An aside: on the Times article

The Times article was, at best, all over the place.

It is incredible how the piece begins with grim predictions (and no specific timeline) for the effects of LLM technology for college-educated workers. Then, it abruptly shifts focus to highlighting small businesses using LLM software. It features interviews with founders from two businesses in Chattanooga, TN and the mayor, and zero accounts from the workers who will be affected.

It’s actually not clear how/why these businesses are featured in a story about LLM-enabled automation. One is a truck parking services startup. The CEO mentioned moving to Chattanooga to benefit from the trucking industry’s agglomerative effects there. The second is a gig/marketplace app that connects buyers in South America to passengers in the US who will deliver their goods purchased in the US. They moved there because their investors asked them to do so. Both are planning to use chatbots to assist customer support reps. That’s the extent of it!

The whole thing read as if the Pulitzer-winning reporter merged a fluff piece for the Chattanooga Chamber of Commerce with an incomplete essay on automation and workers.

Back to the paper

I know I criticized it a good bit, but I liked this paper for applying recent economic history to take a stab at an uncertain future and offer some predictions. It’s a refreshing break from studies that take 50 pages or more to exhaustively establish causal effects well after a major economic event.

A small part of me enjoyed entertaining the possibility that LLM-induced migration would reduce job concentration and political polarization. I’d like to live in a US where gaps in opportunities, amenities and politics between big and small cities decrease. But I have to temper my own excitement with the rest of the sobering story.

While I disagree with the study’s choice of comparisons and some of the consequent predictions, I agree that LLMs have the potential to permanently become a part of white-collar work. For employed workers today, using LLMs helps with productivity at the expense of liability issues. For all workers in the future, the outcomes are still uncertain. Big props to this paper, unlike the Times article, for raising valid concerns about the oligopoly in the development and distribution of LLMs. That the research behind the technology has also grown opaque makes it difficult for academics and other observers to predict how it will pan out.